|

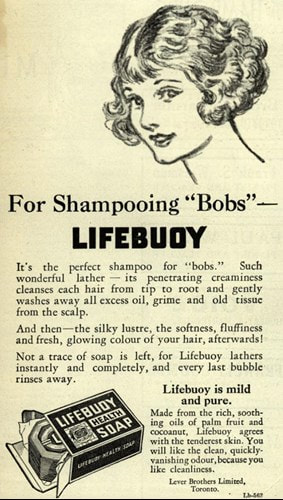

Before modern liquid shampoo became widespread, hair care routines didn’t involve so much plastic waste. Now, we are conditioned (!) to believe we need liquid shampoo in plastic bottles that usually get disposed of rather than refilled, and solid soap is considered a niche. However, thanks to environmental awareness about plastic waste and renewed attention on some of the harmful effects of toxic synthetic ingredients in many liquid soap brands, shampoo bars are making a comeback. But where did the humble shampoo bar come from? And how did it fall out of use? Below we nerd out on the history of the cult zero waste beauty product, explore the role of British cruelty-free beauty pioneer LUSH in “reinventing” shampoo bar in the past two decades, and how we might be looking at bottle-free becoming mainstream again soon. Where Did Shampoo Come From? The word “shampoo” entered the English language around three centuries ago, and it originates from India in the colonial era. It is derived from the Hindi word champo and the Sanskrit root chapati (yes like the popular Indian flatbread), which is to press or knead. The practice of “shampooing” therefore meant to massage the scalp with fragrant oils, rather than hair washing as the word is understood today. The hair treatment was introduced to European societies when colonial traders returned with the local Indian custom of cleansing the hair and body with massage and oils. Shampooing – cleansing the excess oil and dirt from our hair – was also done using other natural methods, such as using vegetable starch and wood ash to absorb excess oil and wash hair. In the 19th century, people also started to use soap bars containing palm fruit oil and coconut oil to wash their body and hair. So the concept of using a packaging-free solid bars to clean our hair isn’t exactly “new” – it has been around for centuries, long before “zero-waste” even became a term. With the dawn of liquid surfactants that scientists created to efficiently remove dirt, a few opportunistic cosmetics companies jumped on the idea of developing products that marked the start of what would become a billion-dollar industry. We started seeing different types of commercial soap displayed on retail shelves in the 1930s and 40s: liquid shampoo, body wash and gels, liquid conditioners – all of which by necessity had to be packaged in containers. At around the same time, plastic as a material became favoured as a replacement for less convenient and more expensive forms of packaging such as paper and glass. The single-use/disposable personal care industry was thus born. The Rise Of Modern Bottled Liquid Shampoo Slowly, these liquid shampoos in plastic containers and bottles became widespread in almost every family bathroom. Though unarguably convenient to use, these products generate massive amounts of waste and neither consumers nor businesses considered the effect off their choices when it came to the lifespan of the container bottles. It is estimated that over a lifetime, the average person goes through 800 plastic shampoo bottles – the majority of which ends up in landfills or in our oceans, which are then further broken down into microplastics, choking marine life and contaminating our own water and food. Needless to say, recycling has never been and continues not to be the answer, with waste regulations and recycling infrastructure mostly unavailable in large swaths of the globe. As reports of the scale of our plastic pollution began to surface and headlines about the massive Pacific trash vortex became more widespread, environmentalists and concerned consumers became concerned about everyday consumption habits and the throwaway culture that was becoming pervasive. This heightened eco awareness saw the advent of the now worldwide “zero-waste” lifestyle, which initially began as niche grassroots concern that later morphed into today’s global movement. How LUSH’s Co-Founder Upended An Industry Over in the United Kingdom, a couple of alternative upstarts were looking to disrupt the personal care industry. In the 1980s, Mo Constantine, co-founder of cult beauty brand LUSH (known as Constantine & Weir, and later Cosmetics-To-Go at the time before they rebranded to LUSH in 1995) was struck by inspiration thanks to an unlikely source: Alka-Seltzer. The fizzing tablets led her to create the brand’s ubiquitous bath bombs, which were also the first product they sold ‘naked,’ aka without packaging. Shortly thereafter, Constantine and Stan Kryszta, the brand’s cosmetic chemist, sought to reinvent the traditional soap bar specifically for hair. Unlike other soap bars on the market at the time, which were based on oils and fats (the traditional recipe for soap), Mo and Stan came up with an innovative formula for a solid version of liquid shampoo. When they first launched their shampoo bar product in 1988 under the Constantine & Weir name, it became so popular that they successfully applied for and won a composition patent for their groundbreaking recipe. Years after the now famous shampoo bar was born in the kitchens that later became LUSH, the brand remains the keepsake of the invention, even though the original patent expired in 2011. Thanks to LUSH, eco-friendly beauty products have been on consumers’ radars like never before, as the brand has captured a (mostly) young and eco-conscious generation with their low waste range and naked store concept, with the brand reportedly saving around 30 million plastic bottles from landfills over the past year alone. Amid a recent public outcry on plastic waste, the company has even launched a carbon positive cork container for the shampoo bars, manufactured using regeneratively grown cork (which absorbs carbon from our atmosphere) and transported via sailboats. The Shampoo Bar Goes Mass LUSH shampoo bars are infused with blends of natural ingredients with cleansing yet soothing properties, such as cinnamon leaf oil, contain no preservatives, and most importantly, do not require any packaging or container. Compared to the average bottle of liquid shampoo, solid shampoo bars last around three times as long and only need be stored on a dish. In recent years, a plastic-free and zero-waste beauty movement has taken hold and become more mainstream. As well as LUSH‘s pioneering range, other independent beauty brands with a sustainability focus have also developed their shampoo bars, many of them featuring natural, plant-based and organic ingredients- brands like Lamazuna (France), Meow Meow Tweet (US) and Ethique (New Zealand) filled Insta feeds the world over with their low-waste, plastic-free modern bars to suit every eco warrior hair type. Even mainstream cosmetics corporations have caught onto the trend and launched eco-friendly and plastic-free beauty products, hoping to catch a share of this budding market. The shampoo bar crazy has also spawned a whole range of plastic-free bars from face moisturisers to pet soaps to hair conditioner, all formulated for various care concerns and all made available sans packaging. In the midst of the many environmental issues the planet is facing, from global warming to biodiversity loss, plastic pollution is one that we can easily tackle individually by making easy switches in our everyday habits. So go on, ditch the bottle and choose the (shampoo) bar- it’s an easy choice you can feel seriously good about. Editor’s Note: This article was updated with more accurate and complete information about the shampoo bar’s 1988 patent filing and origin story. from Green Queen

0 Comments

1/30/2022 0 Comments The Story of Hair: Bouffants, Beehives and Bobs:The Hairstyles That Shaped BritainIt is said that the average woman gets through around 30 hairstyles in a lifetime, with some changing their look entirely every 15 months. Timeshift takes a loving and sometimes horrified look back at the iconic hairdos and 'must have' haircuts that both men and women in Britain have flirted with over the past 60 years. And it's some journey... from the meringue-like confections of Raymond 'Teasy Weasy' via the geometric 'bob' cuts of Vidal Sassoon, stopping off to take in the 'big hair' heyday of bouffants and beehives, and not forgetting the mullet, the feather cut and the ultimate 'bad hair day' look of 1970s perms. Our hair is the one part of our identity we can change in an instant and which speaks volumes about who we are, where we've come from and where we're going. Today, young women are revisiting hair fashions of an earlier generation - big hair and blowdrying are back in demand, whilst many young men sport Edwardian 'peaky blinder' short back and sides. Narrated by Wayne Hemingway. from BBC Four - Timeshift Series

12/7/2021 0 Comments The Story of Hair: The "Blow Wave"If You Blow-Dry Your Hair, You Have This Jewish Woman to Thank If you’ve ever wondered why hood dryers—those domed head prisons so ubiquitous in women’s hairdresser shops throughout much of the ’50s and ’60s—aren’t so common anymore, you can look to Rose Evansky, the Jewish inventor of blow-dry styling who died last month, at the age of 94. Ms. Evansky, born Rose Lerner in 1922 in Worms, Germany, unleashed the revolutionary blow-dry style onto the world from her shop in Mayfair, London then the cultural capital of hairstyling. One day, Ms. Evansky eyed a “barber drying the front of a man’s hair with a brush and a hand-held dryer.” She thought: “Why not for women?” Not long after, the technique made headlines. By brush of luck one day in 1962, the British editor of Vogue happened to drop by Evansky’s shop. Aghast at Ms. Evansky’s technique, the editor rang the fashion editor of The Evening Standard—later that night the newspaper unleashed “the blow wave” onto the world. Ms. Evansky, whose father was imprisoned at Dachau in 1938, and who, speaking only German and Yiddish, escaped Nazi Germany by way of Kindertransport, championed her so-called “Mayfair style”—one characterized by “freedom and movement.” As for her own hair (naturally air-dried) she cut it herself. As she once told W magazine, “Why would I let anyone else when I can do it myself?” Meet the 90-year-old inventor of the blowout Consider if you will, the humble blowout. Freeing us from the tyranny of the bulbous overhead dryers our forebears had to suffer, (curlers digging in to scalps while the heat bears down anyone?), it's both ubiquitous and unique—there's a stylist offering them on every main street, yet no two ways of doing it are ever the same. But where did it all begin? W sat down with the woman behind it all, possibly the beauty industry’s best-kept secret: 90-year-old Rose Cannan. The originator of the woman’s blowout and co-owner of Evansky’s, the leading London salon of the 1960s, Rose’s clientele pre-dates the better-known British salons like Vidal Sassoon and Leonard of Mayfair. Not one to court the limelight, Cannan had all but disappeared until a few years ago when she was “outed” at a cosmetics conference by a friend in the audience who pointed out that she was very much alive and kicking in the British seaside town of Hove. Here she tells us about the day she invented the blowout technique: “It was a Friday and all the chemicals were on the trolley ready to straighten my clients’ hair, yet again. I hated straightening hair. And I remembered something that had happened a few days before. I’d been wandering past a barbershop in Brook Street around the corner from our salon in North Audley Street, and I saw the barber drying the front of a man’s hair with a brush and a hand held dryer. And this image—of the barber with the dryer—flashed through my mind and I thought, ‘Why not for women?’. So I started doing this on my clients’ hair, and Lady Clare Rendlesham (the Vogue editor and famous champion of 60s style-setters) came in, took one look at what I was doing and said, in that formidable voice of hers, ‘What are you doing Rose!?’ and went rushing back out. “I immediately thought, ‘What have I done?’. My usual Jewish anxiety kicked in—Rendlesham could make or break a career. She reappeared with Barbara Griggs, who was a journalist for the Evening Standard, and said, ‘Look what Rose is doing!’ They went out again. The whole thing was mysterious to me. And that afternoon, this piece appeared in the newspaper about the new blow-wave. That’s how it came on the market. “Of course, not everyone was pleased. When the article came out in the paper, my husband [her first husband, the late Albert Evansky with whom she owned the salon] said to me, ‘Have you gone mad? We’ve just bought 20 new hood dryers! What shall we do with them? Throw ’em out?!’ “I do feel like I’ve achieved something. I’ve freed women from having to sit under a hot dryer for ages, frying on hot days—though in the winter it was pleasant enough. I was the opposite of all those male crimpers—I wanted to operate with clients who were mature women who understood what I was doing for them. We chatted, we talked, it was fun. Sometimes they’d say, ‘My husband won’t like this.’ And I’d say, ‘Never mind about your husband, look at it for yourself!’ and I’d give them a little lecture about independence. “Where do I go now to get my own hair done? [Laughs] My hair is best described as ‘windswept’ as I live near the sea. I’ve never colored it, and I cut it myself. Why would I let any one else when I can do it myself?” from W Remembering the Stylist Who Truly Understood Curly Jewish Hair Those of us who have tangled with our Jewish curls owe a debt of gratitude to Rose Evansky, of blessed memory, the inventor of the blow drying technique. Evanksy died last November at the age of 94 – not exactly in anonymity, but her name was not of the household variety, either. You could say that she flew under the radar on a stream of hot air. In the business, however, her name was legendary. Vidal Sassoon, the better-known British hairstylist, once called Evansky “without question the top female stylist in the country and the equal of any man.” If you were a girl with curls in the straight-haired culture of the 1960s, you know from my angst. Hair was supposed to swing, like everything else in the 60s! I inherited my father’s curly hair and struggled daily to tame it, with poor results. If there was an ounce of moisture in the air, my straightened hair would frizz up before I even made it down the driveway. My ringlets were a more reliable predictor of the relative humidity than the meteorologist on the 6:00 news. I would sit on my bedroom floor paging through magazines, cutting out pictures of celebrities with flowing tresses, like Marianne Faithfull, Mia Farrow, and Patti Boyd. Standing in front of the mirror, I’d gently shake my head back and forth, like the model in the Breck commercial – but instead of rippling sinuously from side to side, my frizzy locks steadfastly refused to budge. I tried every trick in the book. Wrapping my wet hair around orange juice cans and sleeping on them was a nightly ritual. When I could no longer tolerate the discomfort, I wrapped my wet hair around my head and secured it with tape. I applied the (probably carcinogenic) Curl Free and U.N.C.U.R.L. products many times, resulting in a flat, chemically burned look. My best friend even agreed to iron my hair – using a real iron from the laundry room – in a process that flattened the ends but left them scorched, too. I’m pretty sure it was after Woodstock that “letting it all hang out” came to apply to hair, as well. Gingerly, I experimented with the new look. The day I emancipated my curls for good was when Carole King’s first album, “Tapestry,” came out. Barefoot with faded jeans and long, curly hair, Carole was my new role model. And then, like a miracle, the handheld blow dryer came into my life. At long last, I could tame my stubborn locks! Evansky, born Rosel Lerner in Worms, Germany, was 16 years old when her Polish father was sent to Dachau and she was hustled out of Germany on a Kindertransport to safety in Britain. Her father survived the concentration camp, and the family was reunited in London the following year. Rose found a position as an apprentice to Adolf Cohen, one of the giants in the hair industry, who also trained Sassoon. She had a talent for the business, ultimately rising to the top of her profession as the most sought-after female stylist in posh Mayfair salons. With a keen understanding of the look women wanted and with their impatience for sitting under a hooded dryer, she came up with the idea of the blow-dry technique. Eventually, she became so successful that she opened her own shop, Evanksy’s, one of the most popular salons of the day. Evansky once confessed to having “Jewish anxiety” when she introduced her new technique, but she needn’t have worried. Both the press and the public embraced it. As inventions go, this one ranks with microwaves and caller ID as one of my favorites. In her 90s, Evansky wrote her memoir, In Paris We Sang, in which she described the harrowing adventures of her early life. It makes me happy to know that out of the darkness, she found fulfillment and success, and was given the gift of longevity to enjoy it. from ReformJudasiam.com

For just about as long as the human race has had hair, we've been coming up with accessories to adorn it with. The history of hair accessories spans a diverse range of styles on both women and men, from bobby pins to brightly colored beads and everything in between. Though, at the moment, hair accessories are only just having a comeback with flower crowns and scrunchies, there have been times when we couldn't step outside without something in our strands. Whether we're pining over our childhood butterfly clips or trying out the latest trends in headbands, those accessories have a storied history full of intrigue. Who can imagine hair without bows and ribbons, barrettes and pins, hair bands and scrunchies, headbands and hair wraps, or clips and beads? If there were nothing to put in our hair, we'd be stuck with our tresses falling in our faces — and a serious lack of style. From the first known accessories in history of ancient cultures all over the world to the modern day pieces we find ourselves using, functionality and fashion have pretty much always been the main goals. Let's take a look at seven key pieces of hair garb that have brought us to where we are today. 1. Ancient Hair Rings Two gold artefacts thought to be around 3,000 years old have been found near Wrexham. These would most certainly be the precursor to our modern day hair elastics and the scrunchies of the '80s and '90s. Way back in the day (think ancient Europe in the Bronze Age) these rings or bands would be made out of solid gold or clay and lead plated with gold. A similar type of accessory was used in ancient Egypt made out of alabaster, pottery, or jasper. It's hard to imagine a circular band to hold your hair back that isn't flexible, but that was how it went until rubber and elastic fabric was invented. I'm pretty thankful I don't have to walk around with a heavy piece of material holding my hair back these days. 2. Hair Bows And Ribbons Though we typically think of hair bows and ribbons as accessories reserved for women and more specifically little girls, fabric used in the hair goes back to when it was especially popular in the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas for both genders. Men's wig ponytails were often tied with a ribbon as seen in all those films set in colonial America. 3. Hairpins Long and ornate hairpins with beads or ornaments hanging from the have been fashionable in many historical contexts. From ancient Roman times where elongated pins were often doubled as containers for perfume or poison to 17th century Japan where kanzashi pins were worn by fashionable ladies, hairpins have served as a way to keep hair tidy and as social status symbols. Eventually, hairpins morphed into what we'd call bobby pins. They first served as a way to keep hair constrained as it was improper for a women to have loose hair showing in Victorian times. They also served as a way to get the finger waves that were so popular in the '40s. 4. Vintage Barrette The more decorative derivative of the bobby pin, barrettes weren't used until the mid-19th century. I remember these were pretty popular in the '80s and '90s, too; my own mother used wear them when I was a kid. 5. Headbands This is another accessory that has its roots in ancient times. Mesopotamian men and women used headbands to keep their hair at bay. In the European Middle Ages, royal woman used metal headbands as a sort of crown. In the early 1800s, it was fashionable to copy the ancient Greek style of wearing headbands, but then hats became increasingly popular. It wasn't until the '20s that headbands starting appearing again, and they haven't really gone out of style since. 6. Decorative Combs Decorative combs are also an accessory that date back to as early as the Stone Age. Many different cultures have used comb-like pieces to secure the hair in place. In more modern times, small hair combs were used as attached to small hat and head pieces in the '50s, and the popular "claw" clips or banana clips made popular in recent decades have their roots in these decorative combs. 7. Hair Beads Beads as a decorative way to adorn braids has long since been an African hair tradition. This look has continued to make its way into modern natural hair trends and styles in Western culture as well. Beads and jewels may not work as a functional way to keep hair fastened, but they continue to be a beloved adornment for hair as a fashion statement. from Bustle

As a conspicuous feature of the human body, hair – or its absence – is also a major element of social perception and identity. Yet the symbolic meaning of hair is far from fixed. Historically, the ways in which this bodily component has been regarded have been astonishingly varied, fluctuant and often contradictory. This is evident in even a brief sampling of the rich lore built by our multifaceted views on hair. For some time, a goodly head of masculine hair was considered the appanage of the warrior spirit. Among the ancients, servants and slaves reportedly had their hair cut very short, in contrast to patricians and free men, who wore it long. By the same token, Germanic kings wore their hair long, but they shaved the heads of the princes they vanquished. One historical account says that, when the son of the Merovingian king Chilperic I (c539-584) was killed, his body was recognised thanks to his long hair. Herodotus tells a story that attests to the relationship between hair length and military prowess. During the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BCE, King Leonidas and his few thousand warriors, including 300 Spartans, were preparing to fight the hundreds of thousands of Persians at the pass of Thermopylae. The Persian commander, who had heard of a small Greek force, sent a spy to find out what they were doing. The spy returned with a surprising report: some of the Spartan soldiers were combing their hair. But the Persians found out that concern for style does not exclude grit, daring and ferocity; the vastly outnumbered Greeks were said to have held the pass for two whole days. An observation by the Greek orator Dio Chrysostom (c40-120 CE), in his brief Encomium on Hair, echoes this association between well-kept hair and formidableness. He refers to ‘hair-lovers’ who take extreme precautions when sleeping on the ground – using a piece of wood to keep their head clear of the earth – perhaps, he suggests, because ‘hair makes them both beautiful and at the same time terrifying’. Certainly, a man who appears dishevelled, as if still drowsy after a night’s sleep, is not as fearful a foe as one who looks spruce, trim and ready for battle. Pioneer pathologists spotted an occasional shaggy heart, and the presumption that cardiac hirsutism correlated with exceptional bravery persisted for a time. A different form of hairiness makes an appearance in the legend of the ancient warrior Aristomenes, who fought against the Spartan oppressors of his homeland. Made a prisoner repeatedly, he escaped his captors each time, demonstrating incredible daring and endurance. When he was finally slain by the Spartans, they opened his cadaver and, marvellous to recount, found that his heart was full of hair. This was not an isolated case in Greek lore. Plutarch told the same of the hero Leonidas; Caelius Rhodiginus, the 15th-century Venetian writer, said the same of the noted Greek rhetorician Hermogenes of Tarsus. Later, when autopsy studies were performed in Renaissance Italy, pioneer pathologists spotted an occasional shaggy heart and, for a time, the presumption that cardiac hirsutism correlated with exceptional bravery in life persisted. However, modern heirs to the likes of Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771), Antonio Vallisnieri (1661-1730) and other founders of the science of anatomical pathology did not inherit such a belief in an anatomical basis of moral virtues. To them, a ‘shaggy heart’ is simply the appearance seen in cases of fibrinous pericarditis. Fibrin is a protein formed during blood clotting. It presents thread-like fibres that, when deposited abundantly during inflammation, can impart a ‘hairy’ appearance to the surface of the heart (including, mind you, the hearts of cowards). These days, no one believes that the heart bears marks of a mettlesome spirit. And, as for the warrior’s mane: male army recruits today know that initiation into military life implies shaving the head. A luxuriant head of hair is considered by some to be proof of effeminacy, something opposite to military culture. Efficiency trumps stylishness: ours is a prosaic age. Traditionally, hair has also been thought of as an ornament, a thing of beauty, an adjunct for seduction – especially in women. Countless odes have sung the silkiness, the golden sheen or the pitch-black, splendiferous charm of the beloved’s hair. Take away the hair of the most outstandingly beautiful woman, and ‘were she Venus herself … she would not be able to seduce even her own husband,’ the Numidian writer Apuleius wrote in his 2nd-century novel Metamorphoses. ‘The hairs are Cupid’s nets, to catch all comers,’ reads a line in the English writer Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). So powerful are the arcane forces believed to reside in women’s hair that an old Scottish superstition reputedly warned that women should refrain from combing their hair at night when their menfolk were at sea, lest doing so cause the boats to sink. Hair’s seductive powers help to explain women’s enduring concern for keeping it luscious, abundant and artfully displayed. At times, such displays have been taken to extraordinary heights. In the Western world, hairdo excess reached its acme during the life of Marie Antoinette (1755-93), the queen of France, who adopted famously complex coiffures, powdered and ornamented with ribbons, feathers, diamonds and more. Her hairdos also became politicised in the form of the coiffure allégorique, with figures alluding to important events. The coiffure à la Belle Poule, for example, featured a complete model of a victorious French warship. Much to the queen’s woe, her hairstyle fancies helped to confirm her frivolity, for which she would pay an inordinately heavy price. Women’s styles continue to enchant today yet, as regards the aesthetics of hair, some have fallen into the opposite extreme – concluding that female charm suffers no detriment from far more minimal hairstyles. The ‘pixie cut’, for instance, held sway in the 1950s and has since reasserted its power several times. The German fashion model Ioanna Palamarcuk has appeared in beauty contests with hair shaved or grown into a meagre crewcut, and so arrayed won the titles of Miss Hanover (2017) and Miss Lower Saxony (2018). Who would deny that, in terms of hygiene, comfort and general good sense, a crewcut drubs the baroque extravaganzas of the Enlightenment era? But we can still heave a sigh for the loss of such florid flamboyance. Men are no less vain than women. Yet, much to their chagrin, hair loss is common as they age. It hardly needs to be said that here, too, societal and individual judgment changes in parallel with the zeitgeist. There is evidence that some in contemporary society see bald men as more dominant than others. Yet the absence of men’s hair has traditionally been experienced as a source of perceived inadequacy. There is much to say about this common blow to the male self-esteem, but I will focus here on one male mental strategy to combat the baldness-induced doldrums: a novel way to regard hair and its caducity. It is owed to Synesius (c373-414 CE), bishop of Cyrenaica and author of an essay praising baldness. An ungarnished scalp, he wrote, is no detriment to a man’s honour; rather, it is a token of wisdom. Look at the busts and portraits of the great sages of the world: if you could put them together, the collection would look like a Museum of Baldheadedness. The sheep possesses the thickest hair among the animals; it is also the stupidest. Youth is the time when hair sprouts most profusely; it is also the time when a man lacks good judgment. When a man reaches the age of sound judgment and keen discernment, hair profuseness is an incongruity. The soul of man, in Plato’s magnificent allegory, is a charioteer who travels through the sky in a chariot pulled by two winged horses. The charioteer would like to climb, way up to the heavens, but the horses pull in different directions. One is a noble courser that obeys the charioteer’s orders – there is no need to use the whip. In contrast, the other one is heavy, ugly, ‘shaggy-eared and deaf’, and does not obey the orders. Why? Synesius suggests that the horse cannot hear because its ears are plugged by its overabundant hair. In sum, hair is a harmful appendage, marking a lack of good sense: nothing to be admired. No bald man today beguiles his frustration reading Synesius’ humorous lines. If his discontent is great, he has such alternatives as Minoxidil ointment and expensive, onerous surgery: the resources of a prosaic age. from Psyche

|

Hair by BrianMy name is Brian and I help people confidently take on the world. CategoriesAll Advice Announcement Awards Balayage Barbering Beach Waves Beauty News Book Now Brazilian Treatment Clients Cool Facts COVID 19 Health COVID 19 Update Curlies EGift Card Films Follically Challenged Gossip Grooming Hair Care Haircolor Haircut Hair Facts Hair History Hair Loss Hair Styling Hair Tips Hair Tools Health Health And Safety Healthy Hair Highlights Holidays Humor Mens Hair Men's Long Hair Newsletter Ombre Policies Procedures Press Release Previous Blog Privacy Policy Product Knowledge Product Reviews Promotions Read Your Labels Recommendations Reviews Scalp Health Science Services Smoothing Treatments Social Media Summer Hair Tips Textured Hair Thinning Hair Travel Tips Trending Wellness Womens Hair Archives

April 2025

|

|

Hey...

Your Mom Called! Book today! |

Sunday: 11am-5pm

Monday: 11am-6pm Tuesday: 10am - 6pm Wednesday: 10am - 6pm Thursday: By Appointment Friday: By Appointment Saturday: By Appointment |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed